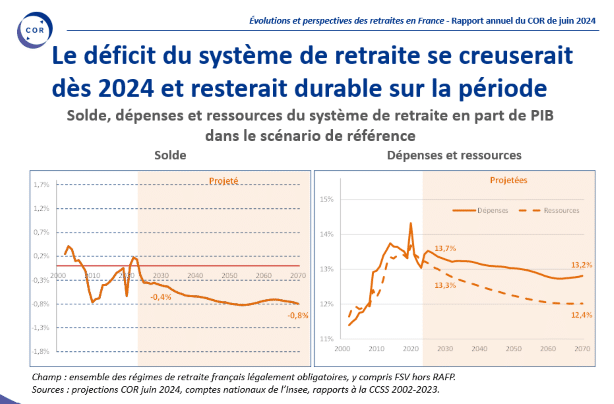

The annual report of the French Pensions Advisory Council (Conseil d’Orientation des Retraites, COR) published early June confirms that the pay-as-you-go system is in deficit. But it is a deficit under control in the long term, from -0.4% pt of GDP in 2030 to -0.8 pt around 2050, stabilised thereafter until 2070. If there will be a deficit, it will not happen because of pension benefits and spendings, which will in fact decrease from 13.7% of GDP in 2030 to 13.2% in 2070. It will happen because of a lack of pension contributions and revenues to finance the system (fall in public employment, erosion of private sector job quality). In this respect, France almost stands out in Europe. Passed the hill of the Baby Boom generation, the demographic shock linked to ageing will not happen in France, unlike most European countries, which will experience a continuing rise pension spending.

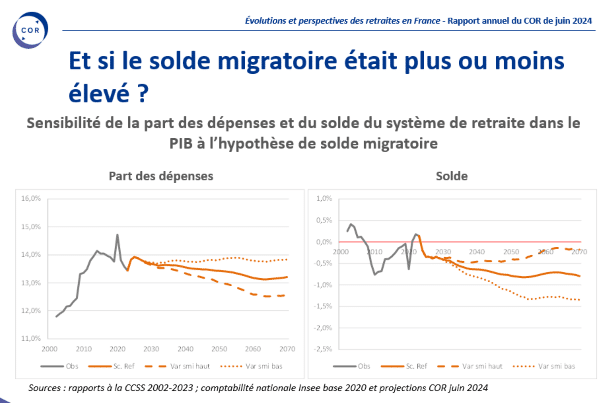

But the most interesting thing about the COR report are the assumptions and alternative scenarios. The report identifies four variables that could influence the course of events: fertility rates, productivity, life expectancy and net migration. An increase in fertility, productivity or net migration, or a decrease in life expectancy compared to the baseline scenario, would more or less rebalance the system. Conversely, a decline in fertility, productivity or net migration, or an increase in life expectancy would aggravate deficits.

Out of the four variables however, only net migration is within reach of government action, the other three variables depend on socio-economic factors that are beyond its control. Government does not “declare” an increase in fertility or in productivity. Migration policy, on the other hand, is shaped by government policy. Migrants are let in, or they are not. They are hosted in a decent way, or they are not. They are trained and have access to skills, or they are not, etc.

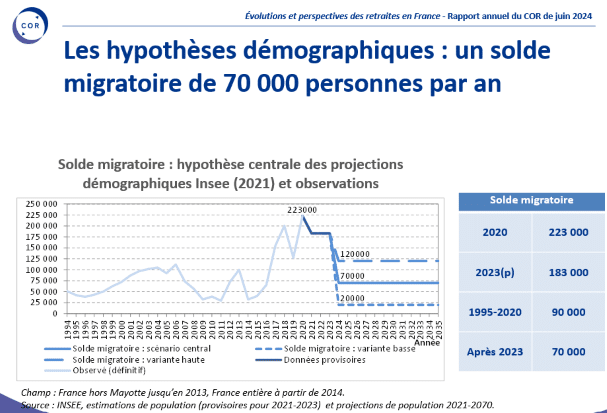

In its reference scenario, the COR expects net migration at +70k individuals per year, which is not much compared to the last few years (+170-200k). In fact, the COR anticipates a considerable tightening of France’s migration policy, with a threefold division of net migration over the next 50 years.

In the alternative migration scenarios foreseen by the French Pension Advisory Council, there is the “zero immigration” scenario, with only +20k per year, which would plunge the pension system into a growing deficit from year to year. And there is an “upward” scenario with a balance of +120k per year, which would reduce the deficit, and get closer to equilibrium by 2070.

The latter scenario is not very ambitious. A +120k balance per year remains well below net migration in recent years. Considering that France receives comparatively few immigrants, there is room for improvement. Indeed, and according to the OECD, permanent immigration (i.e. inflows, not the incoming-outgoing balance) in France stood at +300k in 2022 and only increased by +3.1% between 2019 and 2022, compared to +12.7% for the EU as a whole. As a percentage of the total population, France is also at the bottom of the table, with permanent immigration representing only 0.47% of total population in 2022, half as much as for all OECD countries (1%). Among European countries, only Italy, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Latvia and Greece receive fewer permanent immigrants as a percentage of the population than France.