Shareholder activism, we are told, is on the rise. The number of campaigns, both shareholder value and environmental, social and governance (ESG) oriented, is expected to pick up in the US, while Europe is poised to enter a “golden age” of activism. Shareholder activism emerged in the early 1990ies within the broader movement toward greater stewardship and engagement by institutional investors in listed companies. It essentially remains a US phenomenon although it has spread over many OECD markets. In this policy brief, we go through the basics – the purpose, the deliverables, the ecosystem – and, from there, discuss three aspects:

- The rise of ESG activism is most welcome, but can it successfully break the glass ceiling of “unsuccessful but strong” ESG campaigns?

- The blurring the lines between various forms of activism: do we need better health warnings when shareholder value activism is mixed with ESG activism, and should we move toward a broader notion of “transactional activism”?

- And finally, does it all matter if activism is fighting over shrinking share of the pie? And if the OECD-based widely dispersed listed company – historically the prime target of activism – is becoming less and less relevant in the world economy.

Activism with a purpose

The original purpose of activism is to use shareholder rights to enhance financial performance and shareholder value. Increasingly however, activism aims at ESG objectives and in some cases state-oriented objectives.

Shareholder value

- Opposing / supporting strategic restructuring: related to a merger or takeover proposal, spin-off, or divestiture of business units;

- Returning « excess cash » to shareholders, through share buy-back programmes and dividends and when a firm is believed to have no credible investment opportunities and/or inefficient balance sheets;

- Addressing operational inefficiency through cost reductions, operational improvement programmes and/or new strategic alternatives.

ESG

- Enforcing corporate governance best practices, including: protecting minority shareholders’ rights, ensuring board accountability, independence and diversity, executive compensation and “say on pay”. Non-corporate governance matters include restrictions on political parties spending and lobbying and tax transparency.

- Improving environmental performance, with a focus on climate action and decarbonisation as seen with the rise of “say on climate” campaigns. Other issues include: biodiversity, recycling, land, food and water equity matters, and broader environmental justice audits;

- Improving social performance, ranging from ethnic and gender diversity, to workplace and labour rights issues, and to human rights in the supply chain. Sector specific issues include: access to medicine and vaccines and drug pricing, data privacy, hate speech, consumer addictions etc.

State-led activism

- Gaining access to or influencing the allocation of strategic resources and intangibles in the targeted firm;

- Facilitating enforcement of regulation.

The deliverables

To be successful, activism typically targets firms that (i) are listed on stock exchanges, (ii) have wide dispersed ownership and a good proportion of free-float and (iii) offer minimum level of minority shareholder rights and protection (and by opposition no or little scope for control-enhancing mechanism for block holders).

To achieve its goals, it can basically take two routes: gaining access to the boardroom of the targeted firm and/or ensuring a voice at the shareholders’ Annual General Meeting (AGM). How that happens will very much depend on national regulation and the targeted company’s by-laws. But in any event, it will have to address the collective action problem how a single or a small group of activist investors can successfully gather the support of other investors and stakeholders through engagement and campaigning.

Proxy contest for board representation

Gaining one or several board seats remains the most direct and effective way to influence and help ensure the targeted firm acts in response to the activist campaign’s objectives. This can be achieved either through a proxy contest – presenting candidates on dissident slates when the board members are for approval by the AGM – or through a direct settlement with the board.

Shareholder proposals and vote-no campaigns

Shareholder resolutions can aim at a variety of measures: improving the reporting and disclosure framework, such as say-on-pay and say-on-climate resolutions, the creation of independent oversight committees, reviews, audits etc. Unlike board elections and proxy contests, shareholder proposals are non-binding on the firm. They nevertheless bear significant reputational aspects when they are effectively approved by the AGM but then ignored by management.

Campaigns and engagement

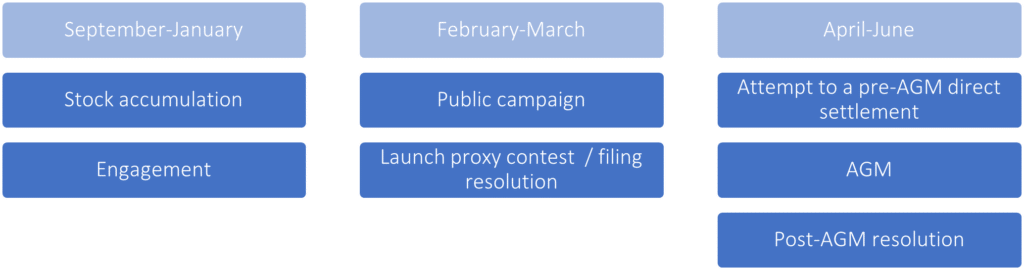

Prior to the AGM season (March to June) lead activists accumulate shares – while staying below disclosure thresholds – and from there will seek to align a broader group of non-activist investors as well proxy advisory firms. They will aim at large passive asset managers, and their index funds, who do not necessarily have the incentives to engage in firm-specific stewardship. A wide array of campaigning tools is used: “white papers” and public reports, open letters, use of social media and networks to communicate with both the targeted firm and the general investor public.

Activism is also backed by shareholder engagement and bilateral communication with the executive management and/or the board ahead of the AGM and more generally during the AGM “off-season” (September to December). Engagement can be particularly effective to reach a bilateral settlement when the cost of bringing the issue at the AGM becomes too high for the targeted firm.

Indicative timeline and building blocks

The ecosystem

The ecosystem can be regrouped in two broad categories: those who pull the trigger and lead the campaign – hedge funds of course, but also a broader group of “governance facilitators” and investor coalitions – and those whose support will be needed: the broader institutional investor community and asset managers, and the proxy advisory firms.

Activist hedge funds

Activist hedge funds are the heart of the matter. Well-known names include DE Shaw, Elliott Management, Icahn Enterprises, Starboard Value, The Children’s Investment Fund, Third Point and Trian Fund Management. Their role and influence are inversely proportional to their economic weight – assets under management (AUM) by US hedge funds merely reach USD130bn. A hedge fund would not hold more than two dozen of companies at any time and would extensively rely on derivatives and debt leverage to amplify voting power and financial gains relative to the economic cost and investment. Hedge fund campaigns are most often associated to the “wolf pack” tactic: informal coordination between several activist funds accumulating stocks and derivatives below mandatory disclosure thresholds followed by fairly aggressive public relation campaign and direct engagement with the targeted firms. Getting a board seat is a strategic goal.

The facilitators

Governance “facilitators” regroup various individuals and not-for-profit organisations that provide principle-based support for generally accepted good corporate governance practices – not least the protection of minority shareholders rights. The US has a long history of “corporate gadflies” individuals dominating the minority shareholder agenda of AGMs. 40% of all shareholder proposals to S&P 1500 companies in 2018 were submitted by them and with a comparatively very good success rate. Small shareholder associations and investor protection institutes serve that function in many countries. In China, the Investor Services Centre (ISC) operating at arms-length of regulatory authorities, plays an important role in exercising shareholders’ right to litigation, mediation and engagement – a function that is essential in China which has a shareholder population of close to 194m individuals, more than the Chinese Communist Party membership.

Investor coalitions

With the years several investor coalitions and networks have been created to resolve the collective action problem. At national level, coalitions typically benefit from the ecosystem of investor stewardship networks: the UK Investor Forum, the US Council of Institutional Investors, the Japanese Institutional Investors Collective Engagement Forum, etc. Regarding ESG matters specifically, the PRI runs several collaborative engagement platforms, whereby a leading PRI signatory launches a campaign for support by other signatories. Alongside other investor networks, the PRI also founded the Climate Change 100+ coalitions with over 500 investors totalling USD54tr AUM. There are many smaller investor-focussed initiatives and networks, such as Investor Advocates for Social Justice (formerly Tri-CRI,1975), As You Sow (1992) in the US and ShareAction (2005) in the UK – and more recent ones – such as Follow This (2015) in the Netherlands, Majority Action (2018) and Shareholder Commons (2019) in the US.

The institutional investors

Institutional investors including asset managers (running passively or actively managed funds) and asset owners (pension funds, insurance companies, sovereign wealth funds) constitute by far the first group of shareholders in OECD economies. Historically, activism has not been part of their DNA. Efforts to promote effective exercise of their voting rights, and the barriers to it have been a recurrent issue over the last 20 years. This is particularly true for passively managed index funds which are overtaking actively managed funds and whose business model does not necessarily reward activism (following an index, not rewarded for beating it, minimizing expenses for lower fees for investors).

Three groups dominate the asset management industry: Vanguard, BlackRock and State Street, a.k.a. the “Big Three”. According to the OECD, they have increased their holdings of listed equity from around USD1.8tr in 2007 to USD8.3tr in 2019, equivalent to 9.3% of global market capitalisation. The potential for “oligopolistic collusion” between these players is possible. BlackRock alone in 2016 was the shareholder of 5% or more of over half of all US listed companies. And yet, despite (or because of) their enormous voting power, their involvement in activism has been minimalist in the past. None of them submitted a single shareholder proposal between 2008 and 2017. More broadly, during that period, average support for hedge fund activism has been far lower for the top ten managers than for the average institutional investor. There is still hope for change. Big asset managers, we are told “are no longer asleep”, particularly on the ESG side of activism. Regarding voting at AGMs, BlackRock recently announced that investors in certain of its index strategies will be eligible to cast their own proxy votes.

The proxy advisors

Proxy advisory firms provide fee-based voting advice and proxy service, and play a central role in activism. The proxy advisory market is de facto a duopoly of ISS and Glass Lewis with reportedly 97% of the market and effective control of 38% of shareholder votes in the US. No activist in the US has ever won a board seat without at least the support of ISS or Glass Lewis. Other services, with a more regional or thematic focus include inter alia Egan-Jones Proxy Services in the US, GIR in Canada, Minerva Analytics & PIRC in the UK, Proxinvest in France, IiAS & SES in India.

Future trends

The glass ceiling of “unsuccessful but strong” ESG voting

The gap between the visibility of ESG activism and its effectiveness has never been that large. Historically environmental and social shareholder proposals hardly ever pass. Just 15 environmental or social proposals went through out of a total of 1658 between 2004 and 2016 in the US, compared with an average 24% success rate for corporate governance related proposals during that same period, and 57% for proxy contests between 2017 and 2020. The average support is slowly but steadily increasing however. During the 2021 AGM season, a number of ESG shareholder proposals would have only needed the support of one or two of the largest asset managers to secure a majority. This raises the issue of strategic voting behaviours: being vocal and supportive when it does not matter, far less when it actually does. In the US between 2011 and 2018, there is apparently evidence that institutional investors’ support would indeed be strong for ES proposals that are far from the majority threshold, but far lower if their vote is more likely to be pivotal.

The regulatory and political agenda at large understandably plays in favour or against the pursuit of activism. In the US, since 2020 the SEC has increased barriers to shareholder proposal submissions, but also introduced the universal proxy card in director election proxy fights, and tabled proposals to strengthen rules on the 5% ownership threshold and to restrict the use of derivatives by hedge funds and on investors’ climate disclosures respectively. The US Department of Labour also set out a proposal to facilitate ESG integration by pension funds. In Europe, the uneven implementation, of the Shareholder Rights Directive II regarding the level and quality of engagement, shareholder rights on executive remuneration and related-party transactions and cross-border voting, as well as the upcoming implementation of the Sustainable finance disclosures regulation’s regulatory standards.

Blurring the lines between various forms of activism

Increasingly hedge funds integrate ESG objectives in their traditional shareholder value-oriented campaigns so as to reach out to the growing concerns over ESG factors by institutional investors. The Children’s Investment Fund for example has, we are told, turned into a “climate radical”. There is also the emblematic case of Engine No. 1 hedge fund which was able to obtain three board seats at Exxon Mobil with just a 0.02% stake following a campaign on Exxon’s financial underperformance and the need to invest in renewable energy.

Hedge fund activism and private equity also continues to blur, with cases of activist funds making bids for the targeted firm, and hence delisting it, and private equity funds venturing into activist-style engagement. Some investors can move back and forth from one approach to the other within a broader concept of “transactional activism”.

Fighting over shrinking share of the pie?

In the medium term, the question remains whether shareholder activism will become a truly global phenomenon or remain a regional transatlantic feature. The centre of gravity of equity has indeed shifted to Asia where the ownership structure and corporate governance rules do not necessarily facilitate activism as compared to North America and Europe. OECD countries have on aggregate seen a net decrease in listed companies every single year between 2008 and 2019. In the US, listed companies are contributing less to employment and to GDP than in the 1970s. At the same time, in 2020, Asia became the largest equity market by number of listed companies, hosting 54% of the total number of companies globally and the number of Global Fortune 500 Companies in China (124) has surpassed the United States (121). Asian companies are characterised by having a controlling shareholder – either a corporation, family or the state.

Regarding ownership structures, while institutional investors remain dominant within the OECD, it is not the case in other markets which has seen a massive surge in state-ownership. Globally, the public sector held USD 10.7 trillion of listed equity as of end 2020, which was almost 10% of global market capitalisation.

Finally, there is the big versus small bias of shareholder activism. As most indices are weighted by market capitalisation, institutional investors managing passive funds tend to favour large companies over small ones. More generally, there is a rich literature on the bias of shareholder activism and engagement toward large listed firms, neglecting the smaller ones (for example here and here ).