The escalating concentration in the digital economy has led to a seriously crowded regulatory agenda in 2022 in both the E.U. and the U.S. While the U.S. Federal-level agenda is much focussed on competition aspects, the E.U. has a broader scope, including data privacy and transfer. Akin to the post-2008 supervision of “too-big-to-fail” banks, the mood is also to specifically aim at systemically important digital companies, aka the “Gatekeepers”. It must be determined who will fall under that category as the designation process is not necessarily too clear. How the regulatory agenda will be converging, or not, between the E.U. and the U.S. in the future is a crucial matter.

A market concentration problem

The rise of large digital businesses reaching systemic size across numerous markets has created numerous policy and regulatory challenges. The topics abound to user privacy, taxation, IPR, consumer and labour rights, disinformation and content online and, not least, competition. A central matter intersecting with most of these issues is escalating market concentration in the digital economy. The proposition that competition is “only a click away” has not materialised aside from some success stories, nor have solutions around the control over data and the impact of digital tools such as AI on user welfare.

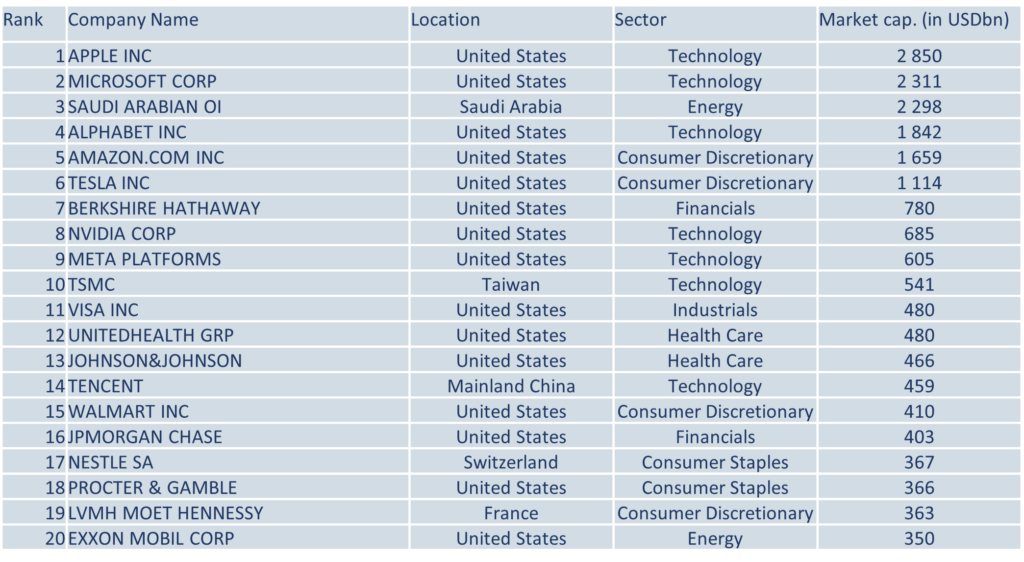

By mid-2020, the market capitalization of Big Tech companies had risen to almost 25% of the S&P500. The expansion in value was undoubtedly boosted by the COVID-19 pandemic and the changing consumer habits since. This increase in market capitalisation boosted appetite for mergers and acquisitions. Between 2010 to 2019 already, each US Big Tech firm spent an average of USD23bn in cash on acquisitions, almost three times more than the average firm in the US Top 200.

Data is the main factor at play behind this excessive level of market. Whether considered as an input to production (alongside other commodities, labour, capital) or as a standalone intangible asset, data allows for:

- High economies of scale (large, fixed costs and zero-bound marginal costs);

- Network effects and self-perpetuating feedback loops (an increase in usage of a digital service will attract more users and increase its value, this also tends to lock in consumers, content creators and suppliers);

- Economies of scope (unlike tangible assets, data is “non-rival” and can be exploited in multiple markets and ecosystems);

- Scaling up effects (exponential value extraction from basic, volunteered and observed data, to inferred data derived using algorithms and mining techniques).

An overcrowded legislative agenda

The policy and regulatory concerns have been rising slowly and steadily in the past decade. In 2013, the tax challenges aspect prompted the OECD and the G20 to launch a fundamental review of international taxation. By 2017, the concept of “platform law” – legislation sitting in between competition and privacy law – had been introduced. Several parliamentary hearings in 2019 and 2020, in the U.S. and the E.U., further brought to light the footprint of digital platforms and the inadequacy of regulation made for brick-and-mortar businesses. National competition authorities launched multiple investigations with varying degrees of success: Amazon and Apple respectively regarding business users’ bargaining power, Meta/Facebook regarding its takeover policy and Alphabet/Google regarding online advertising and search engines. Since then, the regulatory reform environment has become seriously crowded by several legislative proposals in 2022 that are either enacted or likely to be in the years to come.

In the US, the White House released non-binding “Principles for Enhancing Competition and Tech Platform Accountability aim at Promote competition”. And more recently its Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights. Importantly, proposals for bills are lining up at the Congress. Pending the upcoming mi-term elections, some of them could pass through the congressional process, including the American Innovation and Choice Online (AICO) Act, the Open App Markets (OAM) Act and the Augmenting Compatibility and Competition by Enabling Service Switching (ACCESS) Act. Three other Bills that have been introduced specifically aiming a restricting mergers and acquisitions: the Ending Platform Monopolies (EPM) Act, the Platform Competition and Opportunity (PCO) Act and the Competition and Transparency in Digital Advertising (CTDA) Act. There are several other legislative measures at state-level, including in California.

In Europe, four years after the landmark General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) focussing on data protection and privacy, the E.U. embarked on an ambitious agenda, including: the Digital Services Package, consisting of the Digital Market Act (DMA) and the Digital Services Act (DSA); the Data strategy consisting of the Data Act and the Data Governance Act; the Artificial Intelligence Act and a potential AI Liability Act; A Platform Work Directive; and a non-binding European Declaration Digital Rights and Principles.

Several European countries have introduced their own legislative processes, as well as Australia (News Media Bargaining Code, March 2021) and Japan (Act on Improving Transparency and Fairness of Specific Digital Platforms, February 2021).

Aiming at competition matters, but not only

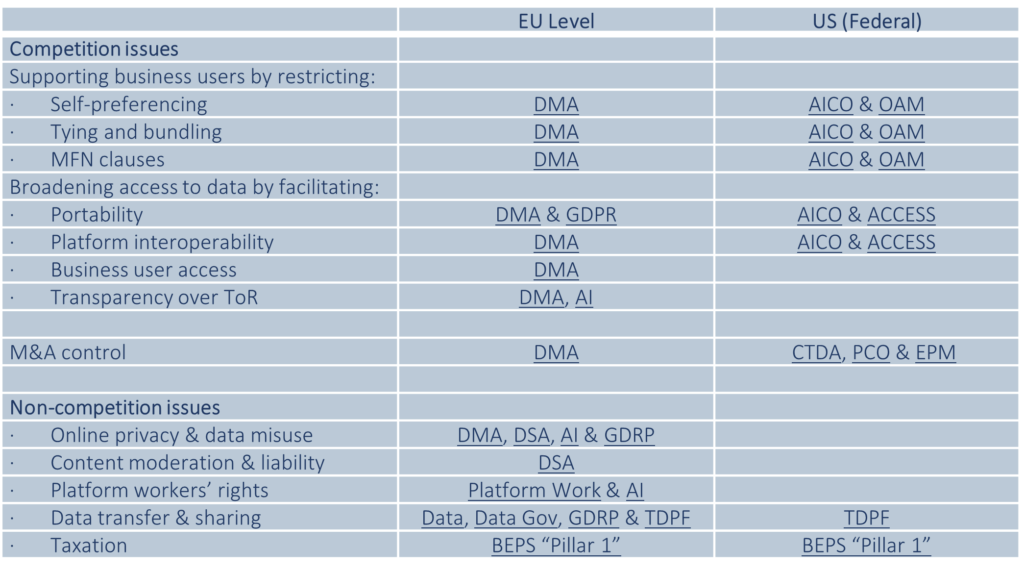

These regulatory initiatives differ in scope and in content. Most of them aim at leveling market power and promoting competition objectives:

- Increasing the bargaining power of business users, through restricting or banning (i) self-preferencing the platform’s own products, (ii) tying and bundling (by allowing end users to un-install any pre-installed software applications on its core platform service) and (iii) restricting MFN clauses (preventing business users from offering more favourable conditions on other intermediation platforms);

- Broadening access and portability of data, including: (i) Allowing data portability (enabling consumers to keep their personal data when switching to alternative providers), (ii) Ensuring platform interoperability, (iii) Allowing business users’ access to data and (iv) Ensuring transparency over user’s terms of agreement;

- Merger control, including prior notice and approval by competition authorities, covering both (i) M&As between direct competitors and (ii) M&As with upstream or downstream firms that relies on that data source.

The scope of these initiatives goes well beyond competition and covers:

- Protecting online privacy and preventing data misuse via explicit user consent on data re-purposing and sharing, and more explicit rules of data access and sharing with third parties;

- Increasing content moderation and liability of platforms (and AI), including by carving general liability exemptions;

- Platform work: preventing misclassification of workers (as independent workers rather than employees);

- Data transfer and sharing: framing the transfer of data between public authorities and private sector providers;

- Taxation: reform corporate income tax rules to account for user-generated value creation and the mobility of intangible assets.

On-going regulatory initiatives in the U.S. and the E.U.

The following table recaps the main initiatives, whether adopted or under consideration, respectively at the EU and at the US Federal levels.

Designating the “gatekeepers”

A common characteristic of the digital regulatory agenda is the emphasis on asymmetrical regulation. Several legislative pieces are specifically targeting “Big Tech” digital platforms, rather than the digital businesses at large. Akin to the post-2008 Financial Stability Board supervision framework for Systemically Important Financial Institutions (aka at too-big-to-fail banks), the intent is to increase regulatory oversight for businesses that have substantial and entrenched market power.

The DMA is specifically designed for “gatekeepers”, businesses in excess of (i) €75bn in market cap or €7.5bn in turnover, and (ii) 45m monthly end users and 10,000 annual business users in Europe, and providing “core platform services” in key digital sectors: marketplaces, social media, search engines, advertising, operating systems, video-sharing, web browsers, cloud computing. The official list of the DMA’s gatekeepers should be disclosed in August 2023. The list is likely to include Alphabet (Chrome, Google, Android), Apple (iOS, Music), Meta (Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram), Amazon (Amazon marketplace, Prime Video, Music), Microsoft (Windows), as well as Netflix, HBO, Sky, Dazn, Spotify (video & music sharing).

The designation process for companies officially qualifying as gatekeepers may become a concern. It has yet to be worked out whether it will build on objectively defined criteria – as is the case for the FSB’s too-big-to-fail systemic banks – or be subject to a discretionary decision by the European Commission. The use of market capitalisation as a proxy for market power is also contestable if the intent is to aim at competition objectives. US-listed companies have higher market capitalisation because of the depth and liquidity of the US equity market and the widespread use of share buyback programmes, not necessarily because of inherent valuation and market power. It is not clear if other groups, unlisted and state-owned companies will also be considered. To give an example, TikTok and Shein platforms are run by privately-held Chinese companies, which do not have a market cap and which asset valuations are subject to caution – estimated at USD140bn for ByteDance (TikTok) and USD100bn for SHEIN. As for Telegram, one of the main messaging services in Europe, very little is known about it. It is officially seated in the British Virgin Islands with an “operational centre” in Dubai.

The need for transatlantic dialogue

How the regulatory agenda will be converging between the EU and the US is a crucial matter – given the size of the consumer (and user) markets and level of integration of two economic blocks. The 2016 Privacy Shield agreement, aiming at stabilising the transfer of data and respect for privacy, has been contested by legal courts and rendered invalid by the ECJ on the ground of the GDPR, leading among others to Google Analytics being suspended in several European countries. While the White House has recently signed an executive order to implement the revised March 2022 Trans-Atlantic Data Privacy Framework agreement, it is not given at all that is will resolve the inconsistencies between the GDPR requirements and US regulation.

Since 2021, the EU-US Trade and Technology Council has precisely the ambition to bring coordination on policy and regulation. Politically, the process for both the DMA and the DSA did not pass too well with U.S. officials, who are concerned about the disproportionate impact on U.S.-based companies. There are also real conceptual differences in regulatory policy making between the U.S. and Europe. Broad principles with ex-post rulings and litigation and class-action lawsuits in the U.S., ex-ante regulation and detailed requirements in the EU.