In the past year, the responsible investment community has gone through more developments than in the previous 10 years combined. By the end of 2023, we should have a new G20-endorsed global standard on Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) reporting, more stringent disclosure requirements for both listed equity and asset managers in both the EU and the US, and corporate duties in supply chains should be reinforced by a new mandatory due diligence framework in Europe.

Old and new policy issues around the ESG will need to be addressed as well: choosing between single versus double materiality approaches, preventing green- and social-washing, rebalancing the pillars of the ESG framework, rebalancing powers and access to data within the investment chain and the uncertain impacts of inflation and the energy crisis.

The policy landscape

The ESG industry has been mushrooming in the past years. Anything between USD1tr and USD30tr assets are considered ESG investing. This is precisely the issue. There are diverging views, definitions and a flurry of standards and initiatives. Despite this, a handful of global forums and norms have been dominating the landscape:

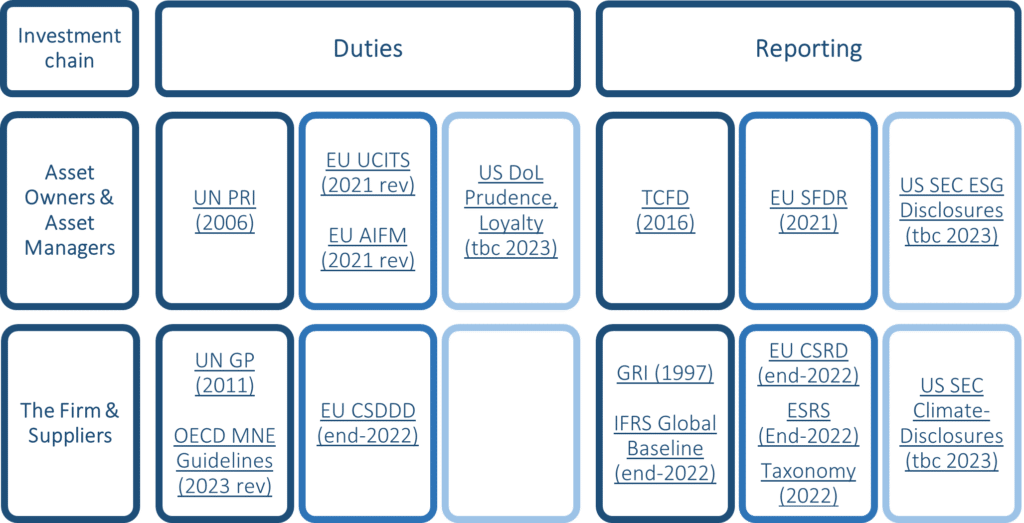

- regarding investor-level commitments and reporting, the UN Principles of Responsible Investment (2006) and, among issue specific initiatives on reporting, the Financial Stability Board Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (2016);

- regarding firm-level reporting, the Global Reporting Initiative (1997) and firm-level duties, the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (2011), the OECD Guidelines for MNEs (2011 revised, and under revision currently) and the IFC Performance Standards on Environmental & Social Sustainability (2012 revised).

Alongside self-regulation and voluntary initiatives, governments and financial authorities have most often taken a hands-off approach and have resisted calls by civil society to shift to mandatory rules. But as of recently they have become increasingly concerned about the level playing field and the fragmentation of the sector. In 2021, the G20 under Italian presidency adopted a roadmap which would look into the supervision and transparency of the ESG rating industry and would push for convergence of standards on reporting. Coming on top of national initiatives, the global regulatory agenda on ESG is becoming crowded:

- Firm-level corporate reporting: there are three separate standard setting processes on-going: (i) globally, the IFRS IOSCO- and G20-backed project of a new Global Baseline of Sustainability Disclosures , (ii) in Europe, a new Directive on Corporate Sustainability Reporting to which are associated new Reporting Standards, and a unified classification system, the “Taxonomy” on climate, possibly followed by a social taxonomy all of which are the EU Sustainable Finance Package and (iii) in the US, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has tabled new rules for the Enhancement and Standardization of Climate-Related Disclosures for Investors;

- Firm-level corporate duties: a new European Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive is in the making, while the OECD Guidelines for MNEs and the OECD Principles of corporate governance are being revised;

- Investor-level reporting: in Europe the Sustainable finance disclosures regulation is being implemented and reinforced by the above mentioned taxonomies, in the US the SEC is proposing new rules on ESG Disclosures for Investment Advisers and Investment Companies ;

- Investor-level commitment and duties: the EU Sustainable Finance Package has already amended relevant collective investment and insurance Directives, and in the US, the Department of Labor is proposing new rules to remove barriers to ESG in pension funds’ investment policies.

The ESG landscape in 2022-2023 (Global, EU & US)

Unresolved issues

By end-2023 we should have more coherence, transparency and better access to information on ESG investments at the global level. For that, the above policy initiatives will need to be implemented and policy coherence between them will be key. Yet, old and new policy issues will have to be addressed.

The single versus double materiality divide

Since its origins, the investment community has been divided between two schools of thought: the “single materiality” and risk management approach (integrating or reporting ESG matters only if it affects firm performance) and the “double materiality” or “positive impact” approach (considering ESG matters that may affect stakeholders of the firm but not the firm itself). This divide was highlighted in a landmark report in 2005 featuring Common Law jurisdictions – where fiduciary duties are sacrosanct – against Civil law and German Law jurisdictions. Reporting framework proposals are inherently different from the IFRS and the US SEC (which are single materiality focussed) to the European one (double materiality). In the UK, there are calls “to split ESG in two” along that divide. This dual understanding is not neutral to stakeholders’ rights and for asset allocation. Single materiality would not necessarily include reporting on scope 3 emissions or labour right standards. And it does not necessarily play in favour of development finance if ESG single materiality creates a bias toward investing in advanced economies. According to Moody’s, 60% of its sovereign credit ratings of developing countries are negatively affected by ESG considerations.

Green- and social-washing

When the scandal of Orpea erupted, exposing widespread fraud and labour malpractices within the French multinational for old-age homecare, the company was fairly well rated on the “controversy risk” scale of a leading ESG rating agency. Green- and social-washing are not new phenomena. Trade unions and NGOs would often expose the gap between corporate rhetoric and reality. But with the growth of ESG funds and their impact on global asset allocation, the stakes are higher for supervisors. In June, the US SEC and German regulator BaFin launched formal investigations following the revelations over DWS overstating its sustainability claims. Earlier in 2022 Morningstar, the global data provider, removed 1200 funds worth $1.4 trillion from its ESG list. The risk for greenwashing is in fact ranked as “the first challenge” by the G20 and its Sustainable Finance Working Group. The issue also concerns lobbying and advocacy by multinationals. In a report recently submitted to the G20 WG, all 30 financial institutions who have pledged to the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero remain members of industry associations which are actively opposing greater ESG disclosure requirements in the US and the EU. In the US, the Republican led “anti-ESG” movement, spearheaded among others by the State Financial Officers Foundation, is gaining traction against the SEC’s initiatives.

It’s all about the E

While ESG frameworks should in principle balance the three pillars, in practice it is almost exclusively about the E as in the transition to a low-carbon economy and biodiversity. The governance dimension most often boils down to mitigating fraud and corruption and to basic corporate governance requirements. Rising issues such as aggressive tax planning are very rarely taken on board, although the investor case is building gradually. Social aspects are also underdeveloped, with too much weight being put on “employee satisfaction surveys” and too little on labour standards as defined by the ILO. There is now an opening to discuss corporate human rights due diligence, with the UN Guiding Principles establishing the framework and the prospect of mandatory duties in the EU (although the US are lagging far behind on this matter).

Access to data and the balance of power along the investment chain

Who calls the shots along the investment chain, linking asset owners to asset managers and to invested assets and from there down the supply chain? Since the 2012 Kay review of asset management practices in the UK, the lengthening of the investment chain and the information asymmetry that goes with it, have been a recurrent policy concern. Asset managers in particular play a pivotal role and can greatly enhance their market power in the face of weak stewardship by asset owners. At firm-level, corporate management also concentrates enormous power, especially when data relies on self-reporting and self-assessment of risks. The lack of access to verifiable open data and, by opposition, the widespread use of proprietary data and algorithms creates barriers to the transparency of the entire ESG sector. It is of particular concern for proponents of the double materiality approach, for whom verification and open data are paramount. The recent hype around open-source intelligence (OSINT) tools, including for human rights and NGO campaigning exemplifies the importance of open data.

Uncertainty around the impact of inflation and the energy crisis What will be the impact in the years to come of the on-going energy crisis and return of inflation? There are different views. On the one hand, there is the traditional belief that ESG practices are inherently in favour of corporate resilience and will help curb pressures arising from energy market volatility (through better use of renewable, lower energy consumption, etc.). There is the opposing view, one that sees ESG practices as “fundamentally inflationary” due to the negative screening (exclusion) practices that lead to reducing the investment universe. “Starving oil & gas producers of needed capital” we are told “is set to become a very dangerous combination that could shatter the global economy. The energy crisis could in fact force a loosening of “rigid exclusionary lists”, by bringing back fossil fuel companies on board of ESG portfolios.